The feud between Kendrick Lamar and Drake highlights technology’s increased role in rap beefs, in addition to how and when AI should be used in music.

© 2024 TechCrunch. All rights reserved. For personal use only.

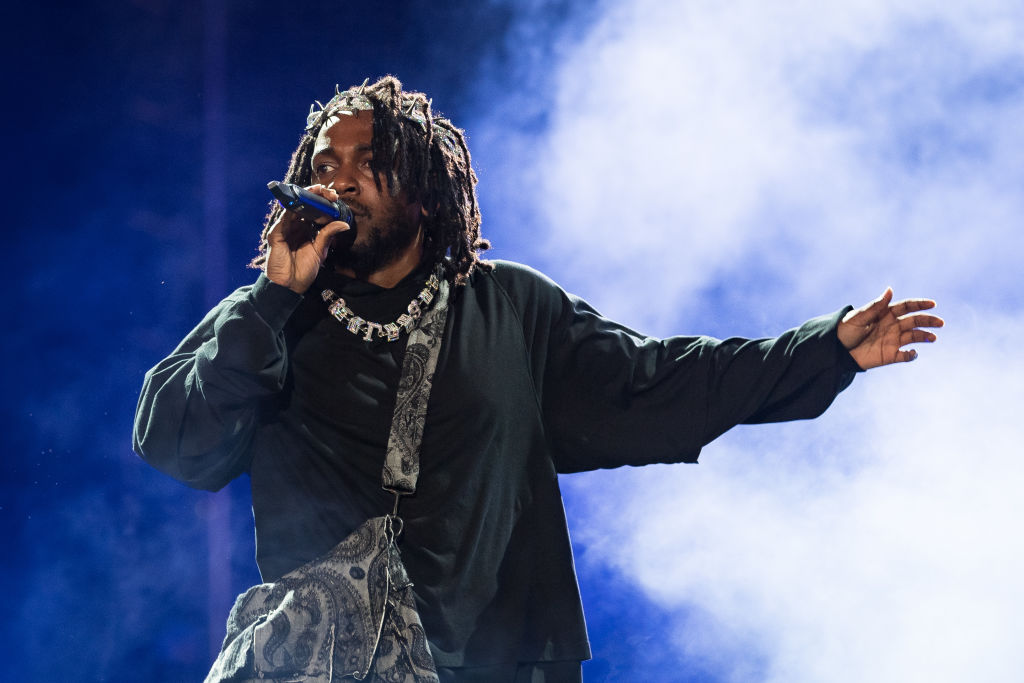

It seems we’re all in agreement: Kendrick Lamar defeated Drake in one of the most engrossing rap battles of the decade. To add insult to injury, Drake also threw himself into legal hot water when he deepfaked the late rapper Tupac.

The tension between Lamar and Drake goes back decades, but this latest flare-up began last fall when J. Cole dropped a song calling Drake, Lamar and himself the “Big Three” in rap. This March, Lamar finally responded, rejecting Cole’s assertion with a scathing verse that dissed him and Drake. The battle ignited, and soon, a legion of other hip-hop artists jumped in, releasing music and taking their sides against Drake.

The weeks-long dispute escalated into one of the most intense rap battles of the digital era. There were side battles (between Chris Brown and Quavo), and white flags (J. Cole apologized to Lamar and deleted his diss response to the rapper). Meanwhile, social media created campaigns and giveaways against Drake, and support for diss tracks against him appeared in everything from Japanese rap to Indian classical dance.

The feud has also sparked a conversation about technology’s increased role in rap beefs, in addition to how and when AI should be used in music.

A pivotal moment came on the track “Taylor Made,” where Drake attempted to diss Lamar using AI vocals from Snoop Dogg and Tupac, a rap icon who was killed decades ago. Drake did not get permission from Tupac’s estate to use the late rapper’s vocals and was threatened with a lawsuit unless he removed the track. Even though Drake took it down, his decision to use AI vocals promoted discussion among music lovers and techies alike.

(Lamar and Drake could not be reached for comment by the time of publication).

Rap battles have turned chronically online

An artist like Tupac, who died in 1996, couldn’t have imagined that artificial intelligence could emulate his voice so convincingly that one of the most popular rappers of the moment would insert it into a song. He also couldn’t have understood how the nature of the social internet would shape the future of music, where “every stream is a vote.”

In the early aughts, rappers had to funnel their diss tracks through radio, releasing physical albums and mixtapes while giving interviews throughout the years of a feud. Responding to a diss could take days at the most, whereas today, it could take mere seconds.

Lamar released a diss response to Drake within 20 minutes of Drake dropping his track against Lamar. Lamar insinuated there were leaks in Drake’s camp that made it possible for him to drop so fast, and that’s a diss in itself. Before the internet was so ubiquitous, that speed would have been impossible.

Drake’s response to his feud with Meek Mill nearly 10 years ago saw him release two songs within four days. But Lamar dropped four songs within five days during this battle, including two in one day. Nobody had to rush out to buy CDs or pull over their cars to listen to the radio, as one founder recalled doing during Jay Z’s infamous feud with Nas. Instead, tracks were quickly dropped on YouTube, shared on Twitter, and then streamed on Spotify en loop.

The speed of these releases does have its downsides: In another viral moment, Lamar’s lyrics confused actor Haley Joel Osment and televangelist Joel Osteen.

Fans have also called Drake “chronically online” during the rap battle, since their real-time posts about the raps seemed to influence him. Some fans accused him of referencing popular tweets and memes people made about him during the feud, then passing them off as his own thoughts and rapping about them. Numerous people online commented that it felt like Drake was writing his responses specifically for his fans to hear, rather than to respond to Lamar. That nearly instantaneous feedback loop stood in stark contrast with Lamar’s raps, which were poignant in their attacks solely against Drake.

This battle is also perhaps the first time such beef has expanded to tech platforms on a wide scale. Lamar fans used Google Maps to virtually vandalize Drake’s mansion, renaming it “Owned by Kendrick.” Streamers pulled long hours on platforms like Twitch, YouTube and Kick, waiting to see if they could be among the first to react to a newly dropped song.

Anthony Fantano, a popular music YouTuber, published no less than six different live reaction videos responding to Drake and Lamar’s songs dropped over the last two weeks. These kinds of reaction videos became so popular that creators are saying that Lamar (or his team) removed copyright restrictions from these songs, meaning they can profit from their videos. This move alone could give more meaning to the role of hip-hop reaction pundit.

AI has entered the chat

The Kendrick-Drake feud is also the first mainstream rap battle to use AI.

Artists across genres are reckoning with the coexisting threat and potential of this technology. Some have embraced AI as an opportunity: The art pop duo Yacht trained an AI on 14 years of their music to create the record “Chain Tripping” in 2019; Holly Herndon and Grimes have both developed tools for other artists to generate AI deep fakes using their voices. Other artists like Billie Eilish, Nicki Minaj and Katy Perry have protested against the use of AI to undermine human creativity.

Consent is a primary concern in artists’ debates about AI-generated music. Artists care so much about what their peers are doing because the use of AI implicates them all — unbeknown to them, their music might be used to train an AI model that another artist is using to supplement their music.

While Herndon is at the forefront of musical experimentation with AI, she also advocates for artists to retain control over their work. She uses AI in her art, but she is also a founder of Spawning, a startup that creates tools for artists that help them remove their work from popular AI training datasets. Meanwhile, chillwave musician Washed Out just released a controversial music video made entirely using Open AI’s Sora, a text-to-video model that has not yet been released to the public.

Tupac’s estate would argue that Drake crossed a line because he didn’t have consent to emulate the late rapper. But Rich Fortune, the co-founder of AI-powered social planning app Hangtight, said it was it creative that Drake was one of the first artists to use AI in a song, especially on a diss track. Fortune says, “There aren’t any rules in a battle.”

“If there were any time to see what the reaction would be, it would be now because punches aren’t pulled when at war,” he continued. He thinks that more artists will now seek to use AI vocals since Drake, one of the biggest artists in the world, effectively sanctioned its use.

In fact, one diss track against Drake in this feud used AI-generated work, and has since turned into a meme against him. Producer Metro Boomin took an AI song called BBL Drizzy and sampled it onto a track that has become one of the rallying cries against the rapper.

Meanwhile, artists as big as Beyoncé have taken a stance against the increasing presence of AI. In one of the few public comments she’s made about her genre-bending album “Cowboy Carter,” Beyoncé said: “The more I see the world evolving, the more I felt a deeper connection to purity. With artificial intelligence and digital filters and programming, I wanted to go back to real instruments.”

Fortune said the biggest hurdle now for artists who want to use AI is just getting permission. Living artists might not be so keen to be AI replicated, but the estates of late musicians might be. The problem there is that many old-school artists who have died, like Tupac, can’t consent to being mimicked because AI-generated music was not a technology conceived before their deaths.

“I don’t know if that’s necessarily a good thing, but it’s the direction we’re headed,” Fortune said about using the work of late musicians. At the very least, he said, it opens up a new revenue source for the estates of the artists who don’t mind them being artificially reincarnated.

The Kendrick-Drake feud also unveiled another point about AI: Its potential ability to emulate artists with a less unique style. Luke Bailey, the founder of the fintech Neon Money Club, said Drake’s more recent music lacks depth. That, paired with the allegations that Drake was so directly and deliberately drawing inspiration from what he saw on the internet, raises the concern that he is doing something that an AI bot could one day do.

“There are two types of musicians: One who can play what someone tells her or him to play and one who can create something original from scratch,” Bailey said. “AI is the former at this stage in its development.”

Bailey is right. Large language models (LLMs), the type of artificial intelligence that powers most deepfake tools, are inherently uncreative. These models synthesize gigantic swaths of data and then respond to a user-generated prompt by predicting the most likely response.

But the most celebrated music often takes the opposite approach: Just look at Kendrick Lamar, a rapper whose bars are so complex that he remains the only non-classical and jazz musician to win a Pulitzer Prize. He’s often regarded as one of the foremost thinkers in music and is known for his commentary on race and politics. AI right now lacks the cultural nuance to form its own thoughts on society, not to mention something as nuanced as race.

“[AI] can’t copy Kendrick’s depth, only his voice,” Bailey said, adding that fans have heard pretty convincing AI-generated Drake songs in the past. “AI doesn’t have any potent bars yet.”

Leave a Reply