Few joys in this cold world can match cracking open a new comic on a lazy Sunday morning. Nothing to do, nowhere to be — just you, a mug of coffee and some sequential art. Not much has fundamentally changed about the American comic book since publishers began collecting newspaper strips as bound volumes in […]

© 2024 TechCrunch. All rights reserved. For personal use only.

Few joys in this cold world can match cracking open a new comic on a lazy Sunday morning. Nothing to do, nowhere to be — just you, a mug of coffee and some sequential art. Not much has fundamentally changed about the American comic book since publishers began collecting newspaper strips as bound volumes in the early 20th century.

Sure, the content has changed radically, but at the end of the day, the basics are still there: characters and text captured in panels designed to be read in sequence. In recent decades, however, the variety of delivery methods has expanded. While the earliest webcomics date back to the CompuServe days, the rise of the digital comic book is more directly linked to the proliferation of smartphones and tablets over the past 15 years.

These days, if it has a screen, you can read comics on it. That includes screens you can strap directly to your face. But as mixed reality headsets have crept toward the mainstream, comics reader apps haven’t really followed. There are a smattering of options available. The Meta Quest store, for instance, has a Korean app called Spheretoon, which is an earnest effort to create content specifically designed for a VR platform (a YouTube promotional video features the hopeful customer quote “way better than expected”).

The lack of options for VR isn’t entirely surprising, as these systems have historically been focused on gaming and other fully interactive/immersive entertainment experiences. From what I can tell, comics fans aren’t loudly demanding a chance to read their favorite titles through their Meta Quest headsets. In terms of focus, however, the Vision Pro is an altogether different beast.

Apple believes, among other things, that it’s a great way to read stuff. This is evidenced in large part by how the company has leaned into the notion of spatial computing as an augmentation of — or even an alternative to — the standard desktop variety. It’s something I’ve started calling the “infinite desktop,” a play on the concept of “infinite desktop” coined by cartoonist and media theorist Scott McCloud in his 2000 book, “Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form.”

Image Credits: Brian Heater

For McCloud, the notion of an infinite canvas is a nod to the unlimited potential of creating art in the digital realm. He was tapping into turn-of-the-millennium hopefulness around the internet’s potential to break art from its physical constraints. Certainly the digital space has transformed many aspects of how art (both the fungible and nonfungible varieties) is created and consumed. But nearly a quarter century after the book’s publication, as Apple has adopted “infinite canvas” to describe its own vision, has the comic book been meaningfully transformed?

Honestly? Not really. Whether you read a comic on paper or a tablet, it’s fundamentally the same experience. That’s not a bad thing — comics are great. One could reasonably make the argument that the printed comic book is the pinnacle of that art form. It’s difficult to disagree, though not for lack of trying.

The Spheretoon example brings to mind the mercifully short-lived trend of motion comics. Much like the U.K. indie pop duo the Ting Tings, they were briefly a thing during the first half of Obama’s first term. In those earliest days of the MCU, publishers like Marvel were pouring money into a format that attempted to leverage emerging technologies by splitting the difference between comics and animation. Think comics panels with some moving parts.

Beyond some of those ambitious but ultimately doomed attempts, technological innovations have been limited to the way some comics are drawn (Wacom tablets and the like) and consumed (smartphones and tablets). At the end of the day, however, they’re the same old comics with a different delivery method.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

Comixology — another early Obama-era innovation — had a profound impact on this side of things. The service combined a dead simple app and a fluid reader with a big store full of digital comics. Comixology Unlimited launched in 2016, giving readers a Netflix-style comics subscription service for $6 a month. In 2021, Amazon — which had acquired the company seven years prior — did what big corporations do to promising young startups: It burned it down and let fans sift through the ashes.

In spite of that bummer of an ending, however, the service had already set the gold standard for reading print comics on digital platforms, and its mark is still very much felt through first-party apps from comics publishing powerhouses like Marvel and Dark Horse. Neither of these seems to be champing at the bit to reinvent digital comics yet again for the spatial computing area, but one of the beautiful things about the Vision Pro’s launch is that minimal developer effort is required to ensure that iPadOS apps work on visionOS.

As such, ported iPadOS apps have made up the bulk of my Vision Pro comics reading. I’ve mostly been playing around with Marvel and Dark Horse apps. The former operates in much the same way as Comixology Unlimited, albeit it for a single publisher at $10 a month (I’m currently enjoying the 7-day free trial period). Echoing the enlightening YouTube quote from above, the experience was “better than expected.” Not life-changing, not the end of my paper comics reading experience, but not altogether bad.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

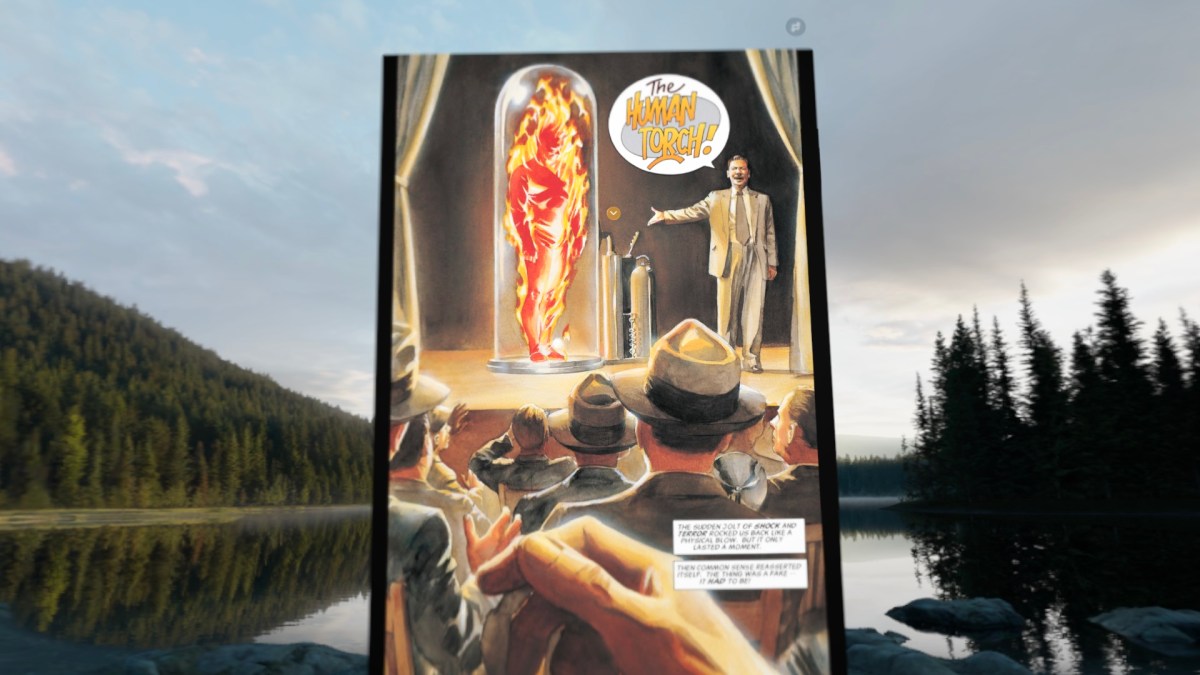

I’m saying this as someone who has limited his Vision Pro usage for reasons described in this article. Reading books on a panel-by-panel basis involves a lot of scrolling and is, on the whole, less than ideal. Expanding them out into a full page and plopping them into the mixed reality zone in front of you, however, is pretty neat. Pop into an environment like Mt. Hood, and you can enjoy a read by a big lake in the middle of a pine forest.

The pages show up big and bright, showing the art in detail via the high-res displays. It’s not game-changing for comics in its current form, but it’s easy to imagine any attempts to innovate the medium for the platform would be the story of motion comics all over again. I’ve lived through that once. I’m good.

Nor would I purchase a subscription to a service like Marvel’s strictly for the purpose of reading on the Vision Pro. If, on the other hand, I already had an active one for my iPad or iPhone, I can easily imagine taking a break from the infinite desktop to find out what the Great Lakes Avengers have been up to for the past 35 years.

Leave a Reply